The Fragility of Progress

I once heard a story about a nine-year-old boy from a hunter-gatherer group who got lost in the forest and survived for a month. He knew which plants to eat, how to find water, how to stay warm, how to avoid predators. None of this was unusual. It was what children were taught.

Most modern adults wouldn’t last a week.

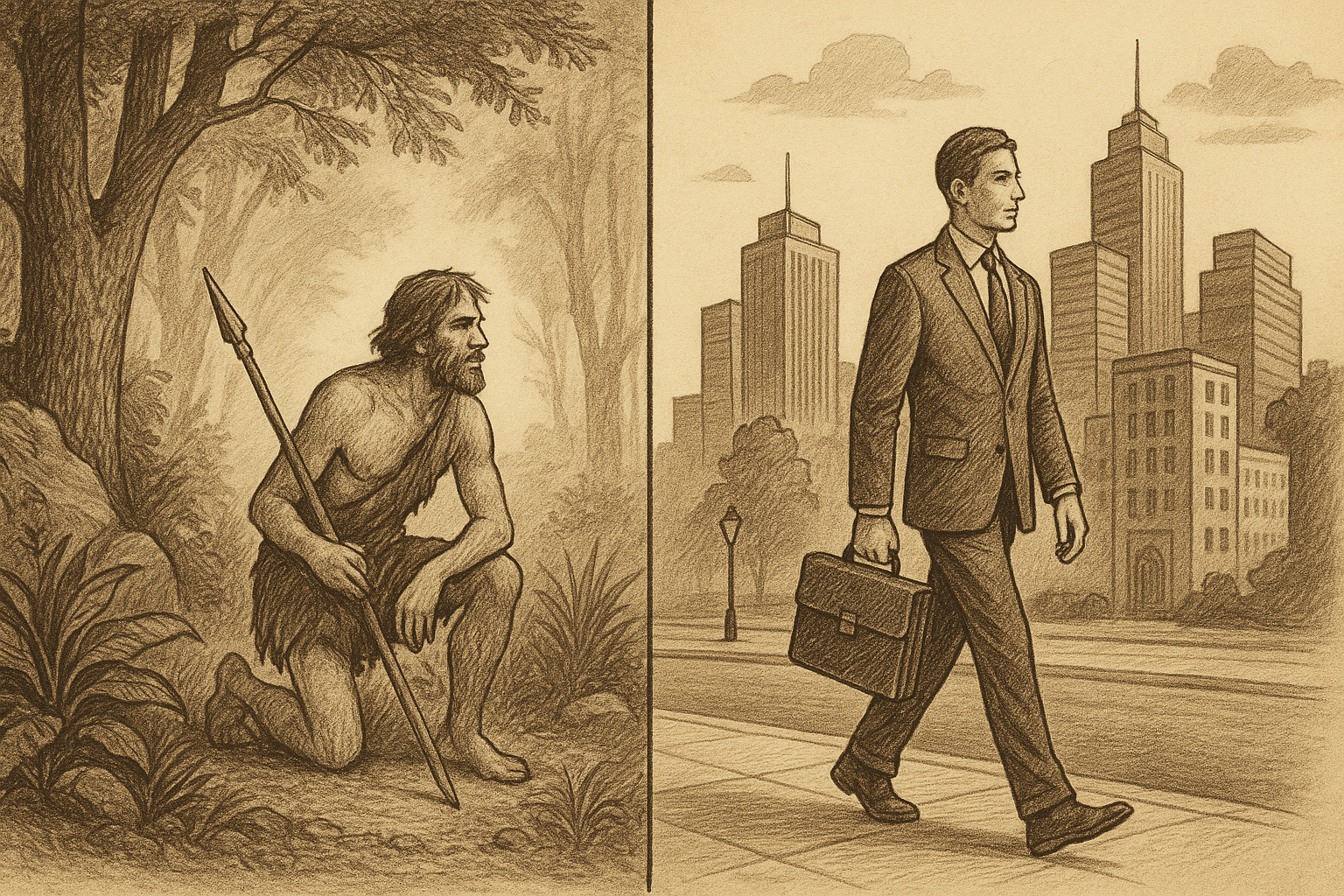

That difference isn’t about courage or toughness. It’s about skills. Hunter-gatherers were generalists. Everyone could hunt, fish, build shelter, mend tools, treat small wounds. They had to. Survival depended on it. But they didn’t go very deep in any one area. Which meant progress was slow.

Modern societies took a different path. We specialised. A surgeon can replace a hip. A chip designer can shrink a circuit. A logistics planner can get your dinner to your door in under an hour. Specialisation lets society accelerate. But it also narrows what individuals can do for themselves. You become brilliant at one thing and helpless at ten others.

This dynamic sits at the core of capitalism. Adam Smith saw it early: the division of labour multiplies productivity. Specialisation is the engine. And companies are built around that engine. At the simplest level, a company gets paid to solve a problem. To solve it requires knowledge or resources you don’t have. The more problems society solves, the more specialised those problems become. Which creates opportunities for even narrower companies to solve them. It’s a loop.

The loop is powerful. It’s why we have antibiotics, safe water, and roofs that don’t leak. But it has a side effect. The more problems companies remove, the fewer skills we practise ourselves. Every solved problem frees us — but also makes us more dependent. When payments go down, or GPS fails, or logistics break for a week, our autonomy vanishes.

Civilization advances by extending the number of important operations which we can perform without thinking of them.

— Alfred North Whitehead

And this is the bargain we’ve struck, often without noticing: society buys progress at the price of individual fragility.

It’s not an argument against capitalism. Capitalism is the best mechanism we’ve found for creating progress. But every system has externalities. This one is built into the logic of specialisation itself.

So what do we do? We don’t need to abandon specialisation, or roll back to farming and foraging. But we can thicken the floor a little. Individually, that means keeping a baseline of general competence: cooking from raw ingredients, learning first aid, fixing small things, reading a map without your phone. Institutionally, it means designing systems that don’t erase all the handles — tools that solve problems but still let you recover when they fail.

The story of the boy in the forest isn’t a model for us to copy. But it’s a reminder. Progress makes us stronger together by making us weaker alone. That’s the bargain. The trick is not to refuse it, but to manage how much of it we want to pay.